A few columns back, I wrote about how I almost died while waiting to start the CAR-T cancer treatment that ultimately saved my life.

But actually, I did die – in a way.

Not in the sense that my organs shut down and I shuffled off to the great unknown. But the man I used to be is gone and it’s not clear if he’ll ever be back.

The uncertainty of it all is killing me, metaphorically.

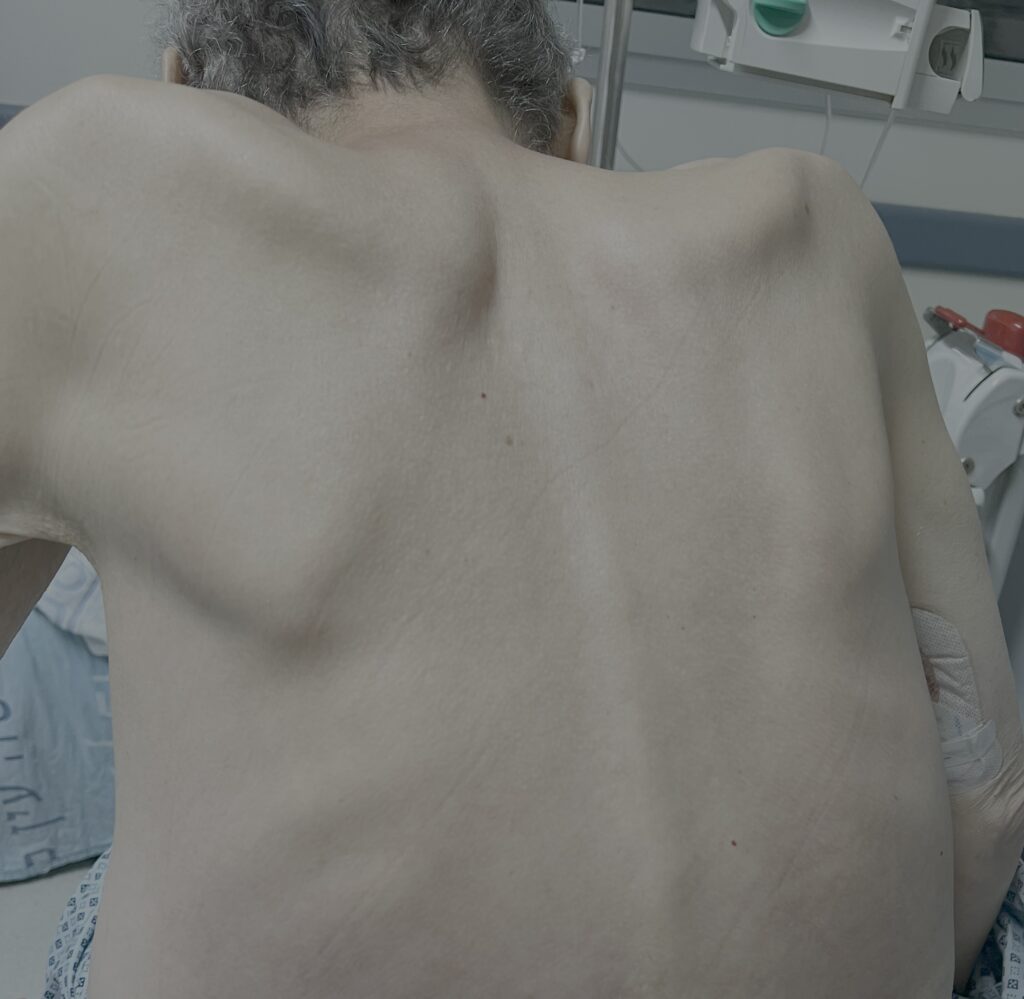

Physically, the road to restoring my strength and regaining the 15 kg I lost has been painfully slow. I still crap out walking after more than 15 to 20 minutes (although when I was first released, I could barely get across the room and always used a cane, even indoors).

It’s not all doom and gloom: I can tell that I’m getting stronger and, in the last few weeks, I managed to gain three kilograms. Is my digestive system “re-setting?”

Still, the ongoing fatigue has forced my wife, Jody, and I to reevaluate all manner of activities that defined our life together before cancer.

How will we travel in the future? My ability and enthusiasm for hiking up the urban hills of Lisbon and Porto, as we did with gusto during our 2024 trip to Portugal, may not return.

Will we become cruise ship aficionados, instead, lounging around the sun deck rather than energetically zip-lining in Honduras? (We actually did that in 2019…as an outing while on a cruise!) For our wedding anniversary this year, we went to a fancy hotel and hung out most of the day at the infinity pool overlooking the Mediterranean.

Beyond the physical, emotionally, our marriage has changed, too. How could it not, with me in survival mode for months, needing help just to get in and out of bed, while Jody was thrust into a caregiving role she never asked for that left her feeling frustrated, discouraged and angry.

“Many carers experience sadness, fear, anxiety, and feelings of isolation,” writes Jonathan Gluck in his memoir, “An Exercise in Uncertainty,” about his own journey with a different but related blood cancer to mine. “Those who are forced to put career, family, or other goals aside may also feel resentment…that can lead to anger about not being able to plan their life, opportunities lost, and dreams deferred.”

I’m not ashamed to say that our marriage of over 37 years also died, in that it won’t be the same going forward. Studies indicate that caregivers and their sick spouses tend towards one of two outcomes: For couples with poor communication skills, divorce is likely; for those who know how to talk to each other, the marriage ends up stronger than before.

Jody and I are committed to landing in the latter category. While my main motivator since I was released from the hospital has been to return – to get back to the normalcy we once had – Jody prefers looking forward: at how we can build a better future.

That fits with something celebrity psychotherapist and podcaster Esther Perel is fond of saying: that most people will go through two or three marriages in their lifetimes…often with the same partner!

Indeed, perhaps the most confounding part of our evolving relationship, post-CAR-T, is living with uncertainty. When a routine blood test exposed a marker that could indicate an early return of my cancer, both Jody and I freaked out. My next PET CT was still several weeks away. (The marker was fine on the subsequent blood draw; was the first one a fluke?)

Uncertainty anxiety tends to follow a U-shaped curve. You worry a lot at the beginning, forget about it in the middle, then worry again at the end, just prior to getting the anticipated news or starting a test or procedure.

In that sense, uncertainty is downright toxic.

Studies have shown that “people who have a 50% chance of receiving an electric shock feel more stress than people who have a 100% chance,” notes Amherst College professor of psychology Catherine Sanderson. Anticipation of pain feels worse than the pain itself.

Similarly, people who are widowed experience lower rates of premature death than people who are divorced. Why? Divorce brings out feelings of uncertainty with people asking themselves “endless questions: ‘Could we someday get back together? Is this person going to get married again? Are we going to have a conflict about child support?’” Sanderson points out in Gluck’s book. “Being widowed is a devastating event…but at least there’s a finality to it. You’re not wondering, ‘Is this person going to be alive again?’”

People who worry that they’re going to lose their jobs in a rumored layoff have more anxiety than those who are actually fired.

Is there any way out of the uncertainty paradox?

It can be helpful to look for silver linings in bad news. This can happen before the news is received, while one is preparing for the worst. Kate Sweeny, a psychology professor at the University of California, Riverside calls this “preemptive benefit finding” or “predemption.”

I’ve never been a big fan of the serenity prayer, but Sanderson stresses it can help with uncertainty anxiety. “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Another suggestion: Become more involved in understanding your situation. “Participants in [Sweeny’s] studies have reported doing things such as getting more familiar with their medical insurance policy, researching the best doctor to see, and investigating what clinical trials are available, even before they receive a diagnosis,” Gluck writes.

I’ll be taking all this into account as we strive to understand the man I am now, eschew uncertainty as best we can, and explore the ins and outs of our “third marriage.”

I first wrote about uncertainty anxiety for The Jerusalem Post.