Zap, crackle, ping.

Dr. Scott Geller is playing Space Invaders with my vision, aiming a high powered (and very real) laser beam into my eyes to “pulverize” the floaters that have made my life an optical misery following complications from cataract surgery in 2019.

Space Invaders, of course, refers to the popular video game released in 1978. But the laser Geller uses is the real deal, not some pixelated version on the screen of a machine in the corner of a dank gaming arcade. And the cost, at $2,500 per eye, is far more than a few lonely quarters spent during a midnight study break at university.

Floaters are a natural part of growing older. Microscopic fibers within the jelly-like vitreous humor can clump together, casting shadows on the retina as they float about (hence the name “floaters”). For most people, they’re innocuous – little black flecks or semi-transparent strands that look like sperm cells under a microscope.

For an unlucky few, though, they can be incredibly bothersome: large grey blobs and clouds of thousands of dots and squiggles that bounce around anytime you change your gaze. Stare them down and they dart away. Ignore them and they show up when you’re least expecting them; tiny flies that you can never escape from but that you’ll find yourself trying to swat away just the same.

My floaters got so bad that it became hard to drive, read or work on the computer. I had both a blob (technically known as a “Weiss ring”) and a cloud that blurred my vision, swishing from side to side with windshield wiper-like alacrity.

The gold standard to “fix” floaters is called a vitrectomy. A retinal surgeon pokes three holes in your eyeballs and drains the vitreous fluid, along with any floaters, replacing it with a saline solution. It’s invasive and eye doctors are generally reluctant to do it.

The laser alternative, vitreolysis, seemed much safer to me, requiring no cutting or recovery period, just some well-aimed, high-powered zaps.

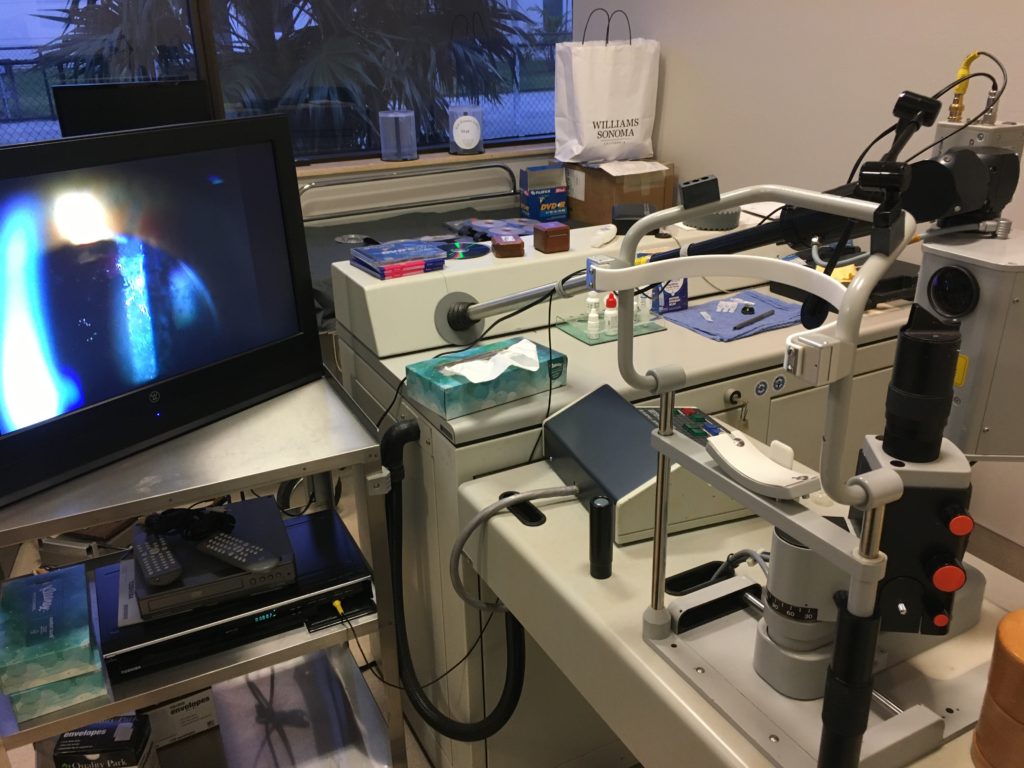

There are only a few doctors in the world that specialize in vitreolysis. Geller is one of the pioneers of the treatment and has done some 20,000 laser sessions over a 30-year career. He uses a Swiss-made laser that costs $500,000. He has two of them in his office in Ft. Myers, Florida, which is where I flew last year to get zapped.

The trip itself was nerve-wracking: Florida during the pandemic has not exactly been the safest place to be and the hassles of traveling under the specter of Covid are not for the faint of heart. But I was determined.

Here’s how vitreolysis works: After I was fully dilated, Geller affixed a contact lens with a metal appendage that looked like a small silver saltshaker to my left eye in order to focus the laser (and keep my eye from blinking).

I leaned into the machine. A blinding light made me squirm.

“Hold still,” Geller instructed, as he adjusted my chin slightly to the left.

Three red beams appeared and began to circle. Those were not the laser, but a tracking ray that helps the operator identify where to shoot.

And then – a sudden flash of red lightning with an audible zing. I could actually see the floaters splatter apart. If my floaters were missiles from Gaza, Geller’s laser would be my tiny Iron Dome.

Another shot, then another and another, 438 in total.

Geller turned to my other eye, which had less floaters and required “only” 96 shots.

“That’s it for today,” Geller said, finally. “We’ll meet up again tomorrow.”

Geller’s methodology includes up to four treatments on subsequent days, as long as there’s no increase in intraocular pressure. (There wasn’t.)

Struggling to see my phone’s screen through my light-sensitive dilated eyes, I called an Uber to return to my room at the Ft. Myers Crowne Plaza.

I climbed into bed where, for the next five hours, curtains drawn tightly shut, my eyes continued to ache and burn; it felt like a knife was stabbing directly into my cornea. I drifted in and out of delirium.

The next day, we did 200 or so shots on the left eye and 47 on the right. Each session, the zaps decreased (the pain unfortunately did not) as Geller tried to break up any remaining blobs and flecks. On the last day, he fired a mere 19 shots.

As the anesthesia wore off after the fourth and final treatment, I surveyed the world around me. The result was…disappointing. Geller had managed to pulverize the biggest gray blob, which was an achievement, but there were now smaller flecks. And he wasn’t able to address the cloud of floaters at all.

Then, a week after the treatment, the gray blob started to re-form.

Geller’s office asks patients to sign a plethora of forms stating that the treatment is not guaranteed to work, so he wasn’t being duplicitous. Geller knows his stuff and deserves his reputation as having the most experience with vitreolysis in the world.

Am I frustrated that it didn’t work the way I’d hoped? Absolutely. If I’d known the outcome in advance, I wouldn’t have made the pilgrimage to Ft. Myers in the midst of a pandemic. But at least now I can decide what comes next from a place of knowledge, with no regrets or second guessing.

Vitreolysis is most appropriate if you have just a small and discrete Weiss ring. If, however, your floaters include a large cloudy haze like mine, vitrectomy may be your only option.

That will be my next step. And this time I won’t have to fly all the way to Florida. There are surgeons right here in Jerusalem, covered 100% by our socialized health insurance.

I first wrote about my adventures in Florida for The Jerusalem Post.