For over 30 years, the name “Botzer” has been synonymous with the founder of the Livnot U’Lehibanot (“To Build and be Built”) work-study program that began in the Old City of Safed. So it was a bit perplexing when posters began appearing around Jerusalem advertising the performance of “Botzer” at the Yellow Submarine music club. Was the ever-energetic Aharon Botzer, who has been running Livnot since 1981, planning on turning to stand up to raise money for the program?

For over 30 years, the name “Botzer” has been synonymous with the founder of the Livnot U’Lehibanot (“To Build and be Built”) work-study program that began in the Old City of Safed. So it was a bit perplexing when posters began appearing around Jerusalem advertising the performance of “Botzer” at the Yellow Submarine music club. Was the ever-energetic Aharon Botzer, who has been running Livnot since 1981, planning on turning to stand up to raise money for the program?

It turns out that the Botzer in question was not program founder Aharon but his son Eliezer who, at 32, is trying his hand as a fledgling rock star. The Botzer Project, as the band is called, has just released its first disc and the Submarine performance is part of the launch tour.

Botzer the band plays an exuberant mix of religious rap and rock, with soaring guitar solos balanced by passionate ballads that sometimes call out directly to the heavens and, at other times, in the best Song of Songs tradition, play out on multiple levels: evocative poems lingering on the love between a man and woman, with the never-far-from-consciousness hint of God lingering in the background, like a hidden camera in the Big Brother house.

Botzer’s song “Mi Atah” (“Who Are You?”) is a good example. The video clip is filled with scenes of urban America and birds soaring through clouds; the lyrics can be easily read both as individually contemplative or religious allegory. “Again you are afraid to deal with the unknown, with yourself, putting on a face, as if you’re in control of what’s happening. Another era of denial.”

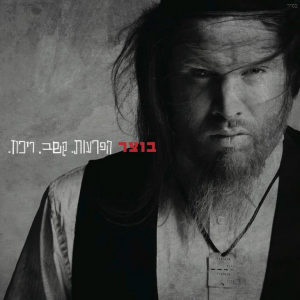

Botzer’s eponymous lead singer is a beast of a man – a hulking giant at well over six feet tall, dressed in an all-black suit that’s a couple sizes too tight, a black shirt and charcoal grey tie, with a velvet black kippa perched high on his head betraying the Breslov hassid he still is. While many ultra-Orthodox religious men sport some kind of peyot (sidelocks), Botzer’s are a wonder – a cascading wall of hair that, if he didn’t turn around to reveal a closer-cropped back story, one would not be entirely mistaken in assuming was the long hair of an 80s metal rocker. Add to this a long pointy beard and various scraggly bits and Botzer is, well, a bit scary on stage.

First impressions aside, Botzer clearly has a talent for communicating – his lyrics are multifaceted with infectious rhymes and he frequently sits himself down on a tall stool to tell stories between sets, mostly of a religious nature. Then he’s back on his feet whirling like a man about to have an epiphany, epileptic fit or perhaps to reveal himself as the Messiah.

The crowd at Botzer’s Jerusalem concert was, with a few rare exceptions, entirely religious, ranging from a smattering of haredi yeshiva students to a mostly national religious/young settler population. That suggests that, in at least its current form, the band isn’t going to be attracting the same audience as, say, rockers Erez Lev-Ari or Ehud Banai, both of whom appeal to secular fans as well.

That’s a bit surprising: Eliezer Botzer the man has been involved in outreach activities to secular Israelis for many years; after serving in an army combat unit, he spent time in India where he established an alternative kind of Chabad which he called Bayit Yehudi (“the Jewish Home”) – no relation to the political party. He lives today in Tel Aviv with his wife and six children.

There’s a personal element too: I first met Eliezer Botzer when he was 3-years-old and I was a participant on Livnot U’Lehibanot in 1984, my first real introduction to both Israel and Judaism. Going to see him in concert was as much a chance to catch a creative new talent as a dose of nostalgia.

Botzer’s freshman album has the clever name of “Attention. Deficit. Disorder.” It can be found online along with a number of YouTube clips, several including English translations.

I asked his father, Aharon, who I’ve stayed in touch with over the years, what he thought of his son’s music? He responded that he didn’t like it at all at first, but after he read the lyrics more closely, “it really grew on me.” If you close your eyes, Botzer’s passion and wordplay may grow on you too.

A shorter version of this article appeared originally on The Jerusalem Post website.